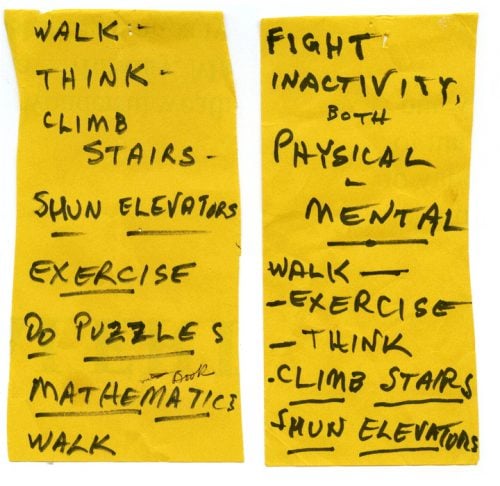

“Shun elevators, take the stairs.” “Do math.” “Go for lunch and see your friends.”

These were the Post-it Notes my paternal grandfather wrote to himself when he began to recognize signs of his own cognitive decline, decades ago. He was a physician who understood the clinical impact of activities that produced neurons and increased blood flow to the brain, and he was attempting to slow the progression of a disease that would someday end his life. He self-diagnosed at a time when access to cognitive assessment was limited. And he self-medicated, via sticky notes, years before studies linked lifestyle to cognitive function, and decades before clinically-validated therapies would arrive. My grandfather’s mind might have been failing, but his instincts were spot on.

After he passed away, and later as my maternal grandmother fell to the same fate from Alzheimer’s, my parents, siblings, and I felt helpless. My father was a physician, as well, whose practice on an Indian reservation made me acutely aware at an early age of the inequities of care and its impact on health outcomes. But in my grandparents’ situation, my family’s relative privilege was of no advantage in the absence of tools or treatment.

Haunted by the lethal prospect of cognitive disease, I saw huge advances being made in treating cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and cancer through screening and behavior change, and had a spark. It seemed that brain health could benefit from the same approach. But there was little medical infrastructure to make it happen.

Then I became aware of Dr. Stuart Zola’s groundbreaking clinical study on Alzheimer’s. Zola, a neuroscientist, found that eye movements, tracked through a camera, revealed essential data measuring the state of cognitive health and the risk for decline. Inspired by what it could mean for advances in early testing, we partnered to found Neurotrack, and this technology formed our initial path toward digital, scalable tests for cognitive health.

However, despite the potential of Dr. Zola’s work, without equal advances in treatment, building a company committed to reducing the rate of Alzheimer’s sounded ludicrous. As one of our early investors told me, “You can’t have a Dx without an Rx.” He was right – more than anything else, the discovery of an effective drug builds out the healthcare system for testing and treatment – but in 2010, no prescription medication existed. No matter the urgency of the need for an aging population, turning a vision into reality didn’t show much reason for hope. After years of unsuccessful clinical trials, some major players shut down their neurology programs. Our early business model was based on providing assessment technology to pharmaceutical companies for trials, and, suddenly, that was over.

So, we shifted our focus. Clinical-trial assessments would still play a role in our future, but we turned to developing technology that would work for primary care – ground zero in the patient-care relationship, and the environment where testing and intervention could impact the greatest number of lives. It became clear that any assessment would need to fit into the tight timeframe and complex logistics of a PCP office visit. Years of clinical research and product development led us to the recent launch of the first three-minute, digital cognitive impairment screening for primary care teams – an accurate and efficient test that is a game-changer, expanding access and ease-of-use to the entire population.

We are now witnessing a transformation in the healthcare system’s approach to dementia, thanks to changes in the payment system, an FDA-approved drug that’s most effective in the early stages of disease, and countless others in development. Detecting cognitive impairment is now a required part of the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit. And while providers may do this by observation alone, PCPs are looking for brief, standardized solutions to improve detection, streamline workflows, and remove subjectivity from the process. Next, I predict we’ll see risk modifying interventions, like lifestyle and behavior coaching for cognitive health, integrated into the system. Routine cognitive screening and intervention are not a growth-stage industry yet, but they will be soon.

I live with the anxiety of genetic destiny, but I don’t think about it as much as I used to. Like my grandfather following his Post-its, I do what I need to do for my brain health, exercising, getting regular sleep, and modifying my diet based on scientific evidence. Things are much better than when we started a company in an industry that didn’t exist. Someday, there will be cognitive testing everywhere and the popular intervention of healthy habits. In all these years, nothing has happened to change my belief.